By JUDITH WHITE

Truth telling and cultural amnesia

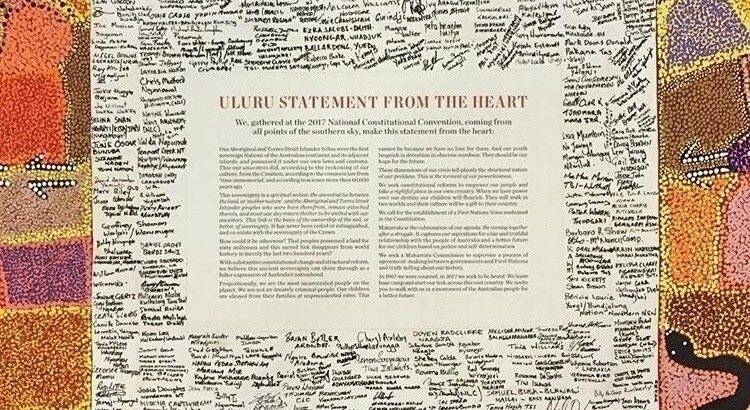

Truth telling was the theme of this year’s Garma festival, held in northeast Arnhemland on the first weekend of August. It’s also a crucial element in the Statement from the Heart made by the indigenous National Constitutional Convention at Uluru last year but rejected by the Turnbull government.

Telling the truth should be a simple matter, shouldn’t it? Yet when it comes to the nation’s history, for those in positions of power it seems to be the hardest ask. No government has yet given it a place among the much-vaunted but ill-defined “Australian values”. Kevin Rudd said sorry for the stolen generation, but didn’t go so far as to address the issue of the British invasion.

Politicians of both major parties are at fault. They hold that the Australian electorate will not support recognition of indigenous history. I believe they are wrong. A simple constitutional change, recognising the millennia of prior occupation of the land and Aboriginal culture, would have majority support in all states when put to the vote. The main proposal of the Statement from the Heart – for a Makarrata (“coming together”) Commission to bring about agreement – does not require a vote, just leadership.

Most nations that consider themselves “Western” have a long way to go in confronting their history. Neil MacGregor, former head of the British museum and now inaugural director of Berlin’s Humboldt Forum, which opens next year, has found modern Germany to be a “painfully admirable” exception. Unlike the British, he says, the Germans “are determined to find the historical truth and acknowledge it however painful it is.”

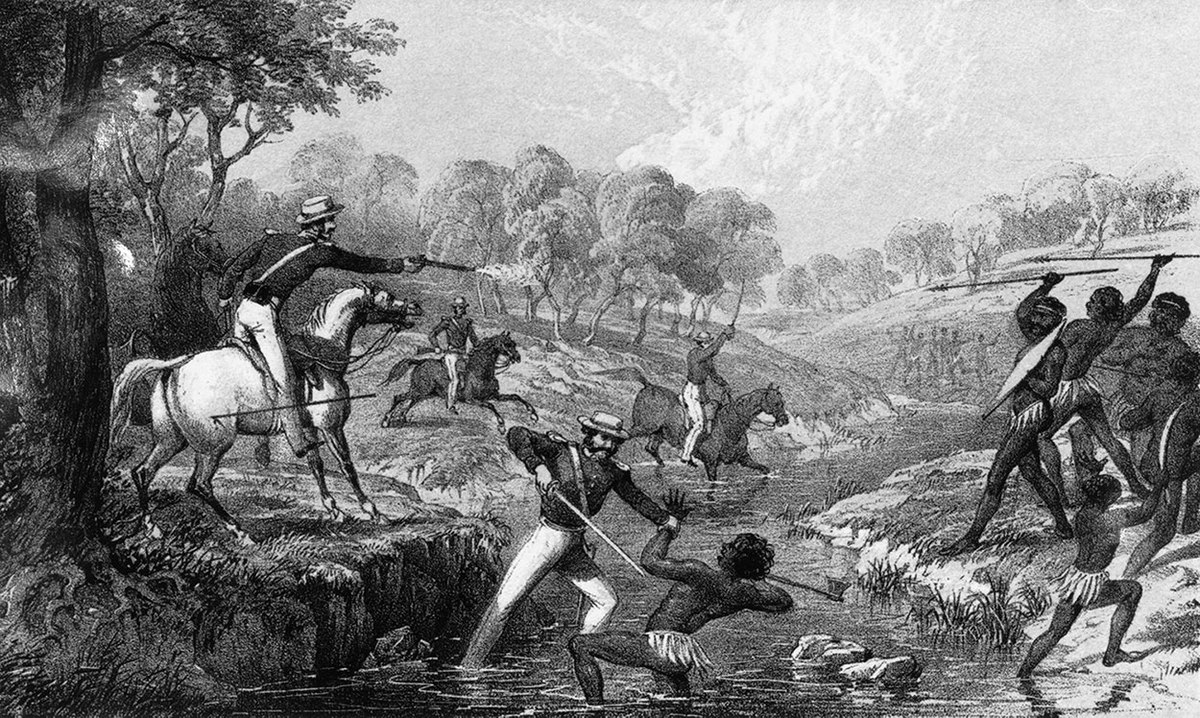

The Slaughterhouse Creek massacre of 1838

Compare that approach with the furore that greeted the opening of the National Museum of Australia in 2001 when then Prime Minister John Howard, his cronies and the Murdoch press attacked its “privileging” of Aboriginal history. Howard, who labelled invasion stories the “black armband” view of history, stacked the board with his mates to pull the museum back into line – and into denial of the origins of modern Australia. (Despite this, the National Museum has gone on to produce some first-rate exhibitions, such as Margo Neale’s Songlines last year.)

Meanwhile millions have been expended on the War Memorial (which director and former Liberal leader Brendan Nelson believes should have a limitless budget), on memorials overseas and on war propaganda in schools, but nothing on the history of the battles on Australian soil.

In fact the country’s true history is now well established and is increasingly understood by thinking Australians – even though, like the science of climate change, it’s still denied by Neanderthal politicians, bigots and the self-interested.

“It is a terrible story,” novelist Richard Flanagan said in his eloquent speech to the Garma festival, “but it is my story as much as it is your story, and it must be told, and it must be learned, because freedom exists in the space of memory, and only by walking back into the shadows is it possible for us all to finally be free.”

There are two crucial lines along which historical understanding has developed: one concerns the 60,000 years of pre-colonial civilisation, the other the British invasion.

“Lest We Forget” … the longest war

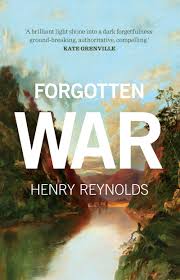

For almost 40 years historian Henry Reynolds has been writing about the frontier wars – Australia’s longest war, fought across the continent. His 2013 book Forgotten War is an excellent summary of his extensive writing on the subject. The conflict involved at least 500 massacres of indigenous peoples; they have now been mapped by his fellow academic Lyndall Ryan. “Lest We Forget”, says Reynolds, should apply to the heroes who fell resisting the invasion, but in Canberra the motto seems to be “Best we forget”.

For almost 40 years historian Henry Reynolds has been writing about the frontier wars – Australia’s longest war, fought across the continent. His 2013 book Forgotten War is an excellent summary of his extensive writing on the subject. The conflict involved at least 500 massacres of indigenous peoples; they have now been mapped by his fellow academic Lyndall Ryan. “Lest We Forget”, says Reynolds, should apply to the heroes who fell resisting the invasion, but in Canberra the motto seems to be “Best we forget”.

What kind of society did the occupying colonists destroy? Even many historians who rejected the official theory of terra nullius continued to believe that the indigenous peoples were “Stone Age” hunter-gathers. This view has now been overturned. ANU historian Bill Gammage wrote in his 2011 book The Biggest Estate on Earth of the “majestic achievement” of Aboriginal land management.

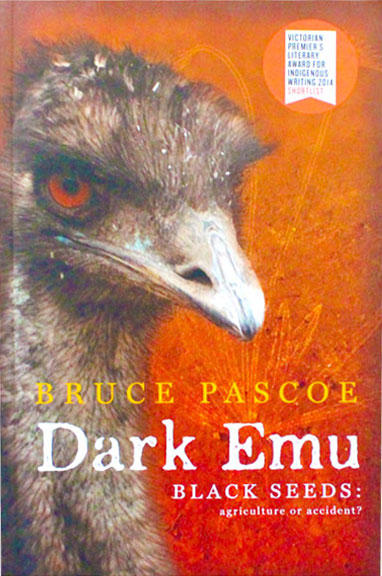

In 2014 Bunorong/Yuin writer Bruce Pascoe took this appreciation a huge step forward with his book Dark Emu. It draws on both recent archaeology and the records of early explorers to show the extent of indigenous achievements in agriculture, craft and construction as well as land management. Dark Emu is now the subject of the most recent dance performance by Bangarra Dance Theatre, has been re-published in the UK and is being translated into European languages. This week Pascoe is in Scotland as an invited speaker at the Edinburgh Writers’ Festival, and then goes on to Berlin.

Perhaps truth tellers, like prophets, are not without honour save in their own country.

Perhaps truth tellers, like prophets, are not without honour save in their own country.

Dark Emu and Forgotten War are both essential reading for anyone who cares about Australian history. They should be on the syllabus of every high school and tertiary institution in the country.

There is a strong tendency in this country for good writing to sink into oblivion. It mustn’t be allowed to happen with these books. As to why it happens at all, I don’t buy the facile answer that Australians prefer sport. A recent panel on ABC-TV’s The Mix, led by author Sunil Badami, raised the question of why so many books are forgotten. The speakers came up with some excellent reading-list suggestions, but the question itself remained unresolved.

I believe the collective amnesia has to do with the fact that writers and artists point us to the hard truths about society. Think Katharine Susannah Prichard, Judith Wright, Nene Gere, Randolph Stow and a host of others. More recently has come a great outpouring of indigenous voices – to name just a few: Alexis Wright, Kim Scott, Leah Purcell, Melissa Lucashenko. These writers give better expression to our unresolved history than all the government reports put together, and they should be celebrated.

The culture heist in NSW

I took a break from this blog over the winter in order to focus on subjects more elevating than the dire state of arts policy in NSW. Matters have not improved in the meantime.

The scandal of the Powerhouse Museum ball, in which $215,000 of public money was spent on a fashion industry event, pales in comparison to what happened next. Director Dolla Merrilees resigned, when Arts Minister Don Harwin should have, and his department announced that there would now be no director but instead a CEO with property and construction experience to oversee the hugely controversial move to Parramatta.

Merrilees and the museum’s Trust bent over backwards to accommodate the NSW Government’s ambitions for the move. Now Merrilees has been sacrificed, the Trust has been sidelined and the needs of the priceless collection, which no longer has a qualified head of conservation, are completely ignored. A major museum has been effectively taken over by NSW Inc as a pawn in its property dealings.

It’s hard to imagine this happening anywhere else but in real-estate- and money-obsessed Sydney where colonisation began in 1788. The government’s decision has already made it the laughing stock of the museum world – see the recent coverage in the London-based Art Newspaper .

The well-informed professionals of the Powerhouse Museum Alliance continue to campaign against the ludicrous move, and the Upper House Inquiry into Museums and Galleries has been asking all the right questions about what dirty property deals have been done, first by Mike Baird’s Government back in 2015 and more recently by Premier Gladys Berejiklian’s Cabinet. The parliamentary Inquiry’s reporting deadline has been extended yet again, to 17 October. But the reasons for the Government’s obstinacy, in the face of expert opinion and public condemnation, remain shrouded in secrecy.

Truth telling? Not in Macquarie Street.

Meanwhile, across The Domain, the Art Gallery of NSW is still waiting for approval of the much-contested Development Application (DA) for its grandiose Sydney Modern building project. Curiously, there was no mention of it in the “Sports, arts and culture” section of Treasurer Dominic Perrottet’s budget, delivered last month. Could it be that a rethink is on the cards – or is the Government simply trying to avert another public brawl, to add to the Powerhouse and stadiums controversies, in advance of the State election on 20 March next year?

One of the few good things I’ve heard about the AGNSW’s plans in recent months is the promise to give more prominence to Aboriginal art in the hypothetical new building. But then, why not build the extension in Western Sydney, where most of the city’s Aboriginal people live? And why not make it part of a broader museum of indigenous history and culture?

It would take a government with vision to back such a plan. But it would be just what this society needs – a fresh approach that puts truth telling front and centre. To quote Neil MacGregor again: “The great thing a museum can do is allow us to look at the world as if through other eyes.” It’s time we looked at our world that way.

SPECIAL OFFER

To purchase a signed copy of Culture Heist: Art versus Money at a reduced price, click HERE.

FOLLOW THE BLOG

For previous posts, click HERE.

Great to have the blog back, Judith. The piece on cultural amnesia is spot on. The books you mention should indeed be on every syllabus in the country. A coalition of writers, readers, publishers, and educationists (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal) should form to put pressure on State Ministers and education departments, and teachers’ unions.

Wonderful piece Judith! I’m passing on….not just to Aussie mates…but to friends in the USA…who have “been there..done that” (remember Wounded Knee?)….

Look forward to many more articles, thank you!

AND ! I didn’t know that the great Richard Flanagan had indigenous ancestry!

Best regards…..\& keep em coming!🥁📣📢🔊🔉🎌

I have become increasingly dismayed at the readiness in Australian society at all levels to accept instances of what amounts to basic dishonesty. As we are seeing in some of our institutions misuse of other peoples’ money or property, civil expectations in orderly road use, queue jumping and much more. Commercial businesses that have adopted the attitude of making money from their customers and cheating them rather that rendering service. Politicians blithely making empty promises that the public accept as normal, but vote for them anyway.

Is this what has come to be “The Australian Way”?

As the late Anthony Newly proclaimed “Stop the World, I want to get off!”

I’d like to see an end to so-called Political Correctness – but I’m hot holding my breath, as they say.

Great to see. should be more of it.

A lot of relevant material on honesthistory.net.au and in The Honest History Book

Welcome back Judith.

Thanks for an eloquent analysis of the self-made mess we are in, Judith.